Here’s a question for you: if I was to give you money for reading this post, what would you spend it on? $100,000 to be exact. Imagine what you could do with that money? Now hold that thought, because I’m going to ask you again after you walk through this thought experiment.

Our economic system is designed to make us think that making more money is a good thing. Society is measured on GDP which is based on the concept of aggregate demand. What we spend reflects what our demand at all price points are for the good and services in an economy, thereby allowing economists to measure the value of the economy (or better said, to price the value of gross domestic product). So if more aggregate spending makes a bigger GDP, then more personal spending is considered wealth.

And bingo, that’s why we have a materialistic society. But without going into the value judgement of that, let’s dig deeper. Because to spend, it means you need money. Money you generate from an income. (It’s why you want that pay rise.) The more money we can make, the better off we are…we are made to think. Because after all, more money means more spending. And more spending results in a enthusiastic nod from the economists that society has a more valuable economy.

Let’s break this down now: what is money? When it all boils down, money is an agreement in society, to represent value (because money itself has no real intrinsic value outside of the raw materials). Therefore, with money, you can exchange that value with something else of value. Which brings me to the question behind this post: what value does money allow us to purchase?

I mean, buying a car is value — but what are we really buying? It is the convenience enabled by this transportation? It is the dignity generated from being associated with an asset?

What value does money purchase?

As humans, we are governed by two instincts: survival and procreation. If we lived in caves with no food stores, we would spend every waking hour trying to generate sources of food. And because all living beings have a life cycle that eventually ends, we’ve developed an instinct in procreation, which I believe is ‘survival’ in a different sense: of the genes, the kind, the species we are. These two instincts are at the core of value that we purchase with value, but there’s more.

We no longer live in caves. We’ve freed ourselves from this burden of daily food generation to enable our being — which in itself reflects a fundamental concept, which is “time”. Significant, because we remove this burden by purchasing time — we go to restaurants and we purchase tomatoes from the super market, buying outputs from the labour of other people who did what we would have done ourselves (what’s stoping you from growing a tomato in your backyard?). But what’s even more significant, is that as we generate value elsewhere in society so that we can then purchase other people’s time (which we would have otherwise had to do ourselves), we end up having more available time. And humans then ask: what next?

Given we have senses in hearing, touching, seeing, smelling and tasting — by activating our senses, we give a sense of purpose to what we do with our available time. Which is why we seek an ‘experience’. The pursuit of experiences give us, at their base level, a sense of sensory fulfillment.

I believe a final super-category outside of survival, procreation, time and experiences is power. Because without power, we cannot control our behaviour. We cannot determine how we use our time. Power enables us to shape our environment in a way which further aligns with our goals in survival, procreation, and stimulating our senses. Without power, we can’t use our time. Freedom in my eyes — one of the key dimensions to success in life — is a combination of time and power: the ability to do what you want whenever you want.

Applying those thoughts

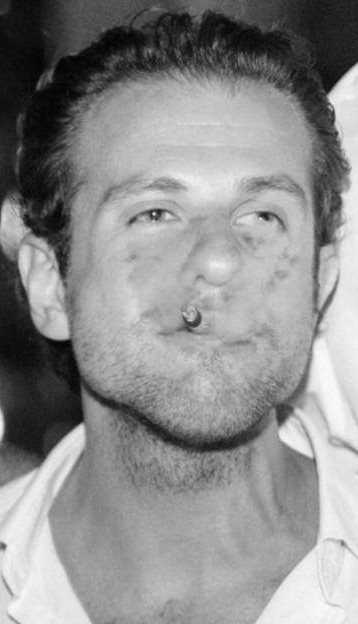

You go to the doctor to ensure you are healthy: that’s survival. But you go to the dermatologist to clear that awkward (but harmless) skin imperfection on your face: that’s your desire to remove an impediment to your status in society, which amongst other things, can impact your ability to procreate. You purchase a car so that you can experience more in life, buy time so that you can do more, and give you a rush due to the sensory excitement of driving — but potentially also to have status which will lead to better procreation opportunities.

In my eyes, of all the things I mentioned above, the ultimate of all value is survival and procreation. To say purchasing time is the ultimate, is not true because it’s simply a means to an end. But time, despite this, is probably the most significant of all the factors for what we purchase. If you dedicated you life to one goal, arguably you will be able to get access to that prize. But it could take years, require other people to assist — purchasing access provides value. Think of how advertisers purchase space in publications: they purchase access to an audience that has taken many years to develop by the mast head. (But if the company, like how Apple has, invests in building its own brand and audience — the need to advertise and access those audiences becomes less necessary.)

I mean hey, who needs to purchase more time when you can survive, procreate, and have your senses stimulated with the power to do so as you please? Well, of course we wil always feel like we need more time: because we will never get enough of a good thing. And which is why time dominates our purchasing decisions.

What do we need money for?

Now let’s me ask that question again: if I was to give you $100,000 for the labour you went through to read this post — what would you spend it on? And when you’ve answered that, is money necessary for you to achieve that?

If money is the goal in your life, then maybe you’ve drunk too much cool-aid from the economists who have mistakenly identified the basis of aggregate demand. Which is done on the assumption that humans have unlimited wants and are only limited in achieving them due to scarcity in supply. And short of disputing the fundamental problem in our society, which is based on an inappropriate theoretical understanding of what us human’s desire in life, just remember this one indisputable fact: money purchases value, but money doesn’t create value (in the ultimate sense).

Benjamin Franklin made the observation that time is money, which as a cliche, is to mean your time is valuable like how it is to making money. I wonder though when he said it, he actually called it out for what it really is.