Last week at the top 100 web applications launch, Ross Dawson made a brief remark that I feel should not go ignored. He said that technology aside, companies like the ones in the top 100 list have a huge impact on our society; They are redefining our society as a whole, with new ways of doing things such as how organisations are structured. On that same panel Duncan Riley was crying out foul about the problem with Australia is that venture capital money is nothing like how it is in the US (which is offered for riskier ideas, at a quicker turnaround, and with bigger amounts) – but a retort made by Phil Morle brought this common whine in the Australian industry to a different level: “You don’t need to be a billion dollar company to be successful.”

In the context of the discussion, this can be taken in several ways about the state of the venture capital industry and its interaction with Internet start-ups, but take a step out of that mindset and instead explore the opportunity with the point made by Ross. Organisations, like incorporated companies of today, are something we should and can re-examine because a billion dollar company is not what the goal should be. Why? I’ll show you.

(Dis)economies of scale

Economic theory proclaims that the larger a company, the better. In the literature, this is regarded as ‘economies of scale ‘ whereby things become cheaper the bigger firms become. For example, the cost of capital is cheaper for a large a company (for those without a financial background, that simply means things like the interest on a bank loan or how much a shareholder expects as a return in dividends or share-price growth) . Operating costs can also fall, which if you think about how retailers will offer discounts on bulk buys – if you are a bigger company, you buy more and therefore get those deals (as well as have influence to create those deals).

Even if you don’t have an economics background, I am sure you are familiar with the concept given the ‘growth’ obsession we have in our world: bigger is better or more is more. However something we should be equally aware of is the ugly cousin: diseconomies of scale . Even economic theory recognises that you can get to a stage where you are just too big, where in fact each extra increase is no longer creating economies but the opposite. It’s a bit like trying to carry the shopping from your car boot: some people can carry a half dozen bags to save on multiple trips; however there is a point where they are carrying too many bags, and the extra benefit of less trips back to the car is in fact outweighed by the increased risk of dropping the bags and hurting their back.

We live in a world, where the growth obsession of our world fails to recognise the ugly cousin. We constantly hear about growth, but what goes up must come down – we never seem to hear when a company is “big enough”. Building on Ross’s point, maybe the answer to that is not that we need to identify the point on the continuum where the diseconomies kick in; instead, the new opportunities offered by technology can instead determine how we can organise resources with the least amount of size.

I have a client that is regarded as one of the biggest advertising agencies in the world. I’m sure anyone with experience with the internal operation of ad agencies will recall how damn complicated they can be – which I think has to do with the ego prominence of the creative industries. Everyone needs differentiation in those industries (and so, the one company is in fact a group of multiple agencies like their own mini empire or stand alone business unit). The complex organisational structure that my client operates in, made me think this is what modern day socialism is like: create a large organisation that becomes so complex, that no one understands it – and in the process, have multiple over-lapping jobs filling functions that are not needed. Giving people jobs for the sake of it. As a case in point, one of the guys in the finance department told me how there was a girl that no one knew what she did. One day she resigned, and whilst one would expect strain on a group with one less staff member, what actually happened was that no one noticed any difference in the output of the team!

Little did I realise however that soon afterwards as I performed a internal (non-client facing) role that this advertising agency wasn’t unique with its socialism. Aside from the fact I’ve met people at my firm that I still couldn’t tell you what they do, my experiences had me see another bigger negative about a big organisation that can be summed up in one word: people. And just like how people by nature are complicated, so too will my answer as to why.

My firm employs 140,000+ globally and about 5,000 in Australia. Whilst that is a high number, more remarkable is the fact it’s a professional services firm: we are not talking about 140,000 high school drop outs but a well educated work-force. As a consulting firm, client facing staff like myself can be in a group as big as 200 people (in each city). There are effectively another dozen or so people with exactly the same skill set and job role as me, but we are just resources that go out to different clients, so ultimately we are doing the same work. That side of my job at my firm has seen me experience a very efficient, lean machine with the fundamental economic concept of “allocating scarce resources” brutally evident with the language of how we run our projects (I even just called myself a resource above, not a employee). However it’s that internal role which had me see the supporting ecosystem for client-facing groups like mine and which made me realise the weaknesses of a big company. I couldn’t tell you how many of the 140,000 people are supporting the client-facing professionals, but I would hazard a rough guess to be about 20%. The nice way of saying it, is that in Porter’s model , that 20% are the support staff to help execute our primary revenue-generating activities. Another way of putting it: that 20% are the overhead.

Overhead matters for two reasons in this discussion: it slows down an organisation (ie, decisions) and it can definie its existence (ie, costs). Each of these points are worth looking at separately.

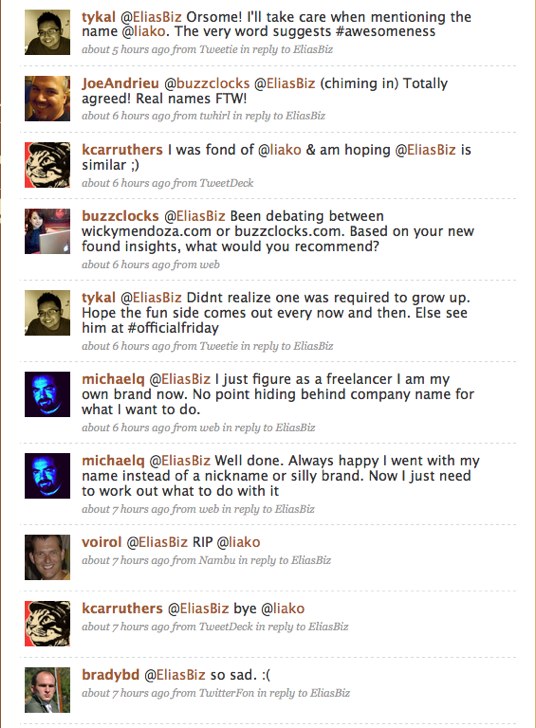

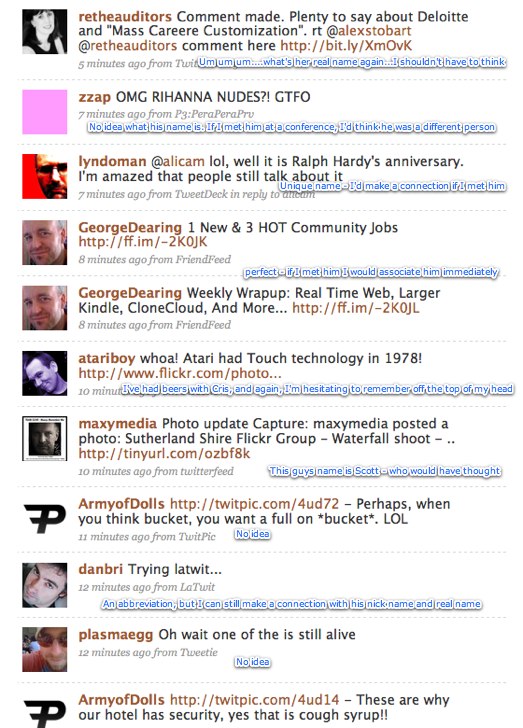

“Frustration” defined: the sum of all people you need to work with to get something done in the last month

People and decisions

That internal role I discussed above, was about implementing a new technology at my firm. I could write a book about the experience, but suffice to say I can recall one incident which is a perfect reflection of something I learned about getting something done in a big company.

This particular technology allows you to add extensions that can drastically alter the functionality of the product. These ‘plugins’ are remarkably simple – we are talking about uploading a single file that is perhaps 50kb (smaller than a typical word document) – and once uploaded via an admin interface it can be activated for immediate effect (with documentation fully provided on the web). Indeed, in the early days of the technology’s roll out, I would often add new plugins as I felt the need arose, but that quickly ended when I was forced to concede that’s not the right way to do things (as it’s not my job). So therefore, if I ever wanted a plugin, I would have to e-mail the IT guys, who would then review it, test it, and then upload it. This is fair enough because adding a plugin could destabilise the system losing valuable data.

I might also add whenever I sent those e-mails after I no longer installed those plugins myself, I would follow up a few weeks later only to find no one had got around to doing it.

Why the significance of this story? Something that I could do in 30 seconds instead takes weeks because I work in a large organisation. For example:

– write an e-mail asking for the request explaining why: 30 minutes

– following up on the status of my request: 60 minutes of e-mails, listening to justifications for inaction, etc

– escalating to a superior when I felt things were taking too long: 60 minutes of meetings and e-mails, as I stressed the importance of a particular plugin for the productivity of one of our pilot groups

…And that’s in raw effort. That’s not accounting for the time stretch of a few weeks (actualy months in one of the cases).

Even though I had the skills, understanding, access, and ability to do this – I couldn’t due to lines in the sand of what I was allowed to do. And because I couldn’t, what would take 30 seconds for a small start-up using the same product, it would in fact take me hours upon weeks to get another few people whose “job” it is to do it.

This example is more humourous than harmful, but when it comes to large organisations, it’s a perfect characterisation of how things get done. I can assure you, all big companies work like this – by definition, a company that is Sarbanes Oxley compliant has so many segregation of duties it will make you cry with laughter. If I shared with you some other stories, that laughter will turn to shock, when you come to the truth of how companies actually operate.

People and cost

At another one of my clients, they have been undergoing some massive growth over the last few years, with a large organisational re-shuffling as this rapidly growing company took shape. A guy I’ve got to know that’s been there a while (and which I might add, we have no idea what’s he actually does as a job despite his title) told me something quite funny. His observations over the years, is that as a company increases in size, so does a corresponding increase in headcount irrespective of any other factor. By example, he explained that lets say a new person is appointed to lead a new team – they now require a personal assistant. And that new team now needs a dedicated IT guy. And then an HR representative. And the list goes on – rather then a company consolidating on its size (ie, merging job roles to avoid duplicity), what he thinks is that as the company has grown over the years, there is always a corresponding increase in head count regardless without any obvious reason why. It’s almost like a natural externality of growth is headcount.

Payroll is a significant cost for any company which can be up to 80% of the total expense of an organisation (my former headmaster told me that, that being a knowledge intensive organisation: a school). So as my above discussion highlights, I obviously find it amazing how such a significant cost is not controlled because management don’t actually understand what staff they have (and as an aside, current enterprise social networking technologies specifically target the real need of documenting what expertise a company’s staff actually has because no one knows). Whilst this may seem like an important point from a controlling costs point of view, I wish to raise it’s actually a hell of a lot more significant.

Let’s say a company needs one million dollars a week to pay for things like wages, electricity, office rent etc. In other words, a company needs sales of minimum $1million a week purely to stay alive – to pay for the stuff that in theory is meant to help it make money in the first place. This is without regard to meeting profit targets as expected by a company’s owners and other such factors. If that company can’t cover that $1million, it is technically insolvent. Meaning, jail time for the directors and senior management for running such a company.

So if a company has these commitments, it ties their hand. They suddenly become very risk-averse; where experimenting with a better way of doing something may threaten their ability of making that $1 million a week. Couple that with the fact that most organisation’s single biggest expense is payroll, with lists of employees that no one person exactly knows what they are doing, and it makes you wonder. Companies effectively exist to cover their expenses, but if they actually dug down, they’d realise those expenses may not even be something that require. In effect, a company’s entire strategy and positioning in the market (ie, prices that take into account enough to cover overhead) may be dictated by something that might not be needed. A big company exists purely to feed the beast, making decisions that may not be what a company should be making if it didn’t have to worry about its overhead.

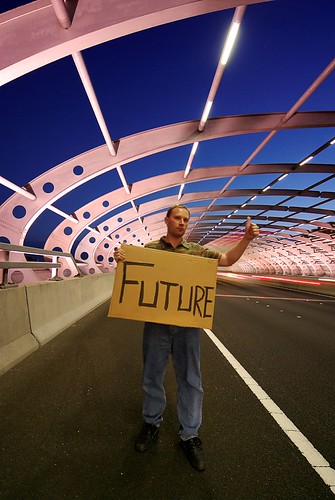

Small is the new big

The power of 12

Going back to how technology is enabling us new ways of organising, if the only reason why a company needs to get big so it can get economies of scale, why don’t we flip it? We no longer live in the industrial era where economies of scale are the goal. Instead, the biggest cost we have now is time; if the expertise is in the people we employ, we need to scale operations so as to give them money and working conditions that suit their lives. This isn’t relevant only for professional services, but for any web service – the fact you provide a service and not a manufactured good means its driven by people not metals.

Of course, a company’s strategy can either be cost-competitive (like Dell) or differentiation (like Apple). But this doesn’t negate the fact, that a company should only have costs that directly add value for the customer (which is why we have innovations like activity-based costings which allocate overhead directly to customer activities, but that’s another story). Given that people are the biggest expense in companies now, we need to question, do we really need that many people to provide that value?

I have a rule I follow in life which has grown out of my experience with how things go wrong: complexity. The more factors, the more likely something is going to fail. For example, if you are driving to a wedding – the more traffic lights, the more likely it is going to slow you down. The longer you have to drive, the more likely you will get involved in a car accident. If you need to drop something off on the way to the wedding venue, if you need to make two separate stop-offs, the more likely you will be late as opposed to one drop off (regardless of the distance, but based purely on unforeseen variables). So basically, you need to minimise the ‘nodes’ in the line. Even when things look they are fine, the more variables to success, the increased risk of something happening that will distract that goal.

However, I am willing to concede, you can’t be a minimalist for everything, which is why I am settling for the number 12 – keep your variables, especially people, to a maximum of 12. Aside from religious connotations which makes the number so omnipresent in our lives, the reason I like it is for the same reason it’s the base number of measurement systems used through history , like the still dominant imperial measurement system. That reason being, it’s one of the most versatile numbers. Versatility and agility to the market is what success is now; not economies of scale.

If designing an organisation, you want a core team of 12 people. Those 12 people together, should be able to do everything that needs to be done to meet the needs of the customer. And if the organisation needs to scale for whatever reason, then those 12 people should have specific functions that they own. The number 12 is magical, because for the same reason it was used in the measurement systems in the past, it is so versatile: you can re-group your 12 people into even teams of two, three, four or six. Don’t underestimate the impact team dynamics like that can have – or using a term that Mick Liubinskas says as often as a nun does her Hail Mary: it emphasises the importance of “focus”, in an agile way that can easily adapt to situations. Yet at the same time, you will find with 12 you can get almost anything done if you truly have a talented team. Still don’t get 12?

The number twelve, a highly composite , is the smallest number with four non-trivial factors (2, 3, 4, 6), and the smallest to include as factors all four numbers (1 to 4) within the subitizing range. As a result of this increased factorability of the radix and its divisibility by a wide range of the most elemental numbers (whereas ten has only two non-trivial factors: 2 and 5, with neither 3 nor 4), duodecimal representations fit more easily than decimal ones into many common patterns

Source: Wikipedia

There are dozens and dozens (whoops, was that 12?) of companies that are small but successful . Challenge yourself: does world domination really equate to a 15,000 person workforce? Focus on getting 12 highly capable people, and you will avoid entering the trap of the big companies today that are slaves to their own existence. We have technology today that could design a radically different organisation in 2010 completely foreign to how traditional business operates. If you explore what smart people have said to complement what Ross originally meant by his comment, you now might also realise that those top 100 web applications represent more than meets the eye.