The Information Value Network is an economic theory for Internet businesses, which incorporates my original thinking of the Information value chain. It describes how data openness, interoperability and data portability allows for greater value creation for both service providers and their users. It is proposed by myself, and is inspired by two existing theories: David Ricardo’s 1817 thesis of comparative advantage and Michael Porter’s 1985 concept of the Value Chain.

The theory on information value-chains and networks

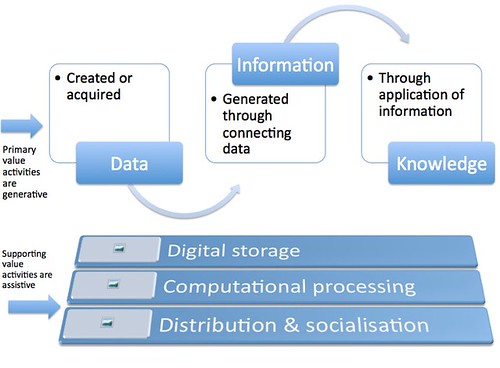

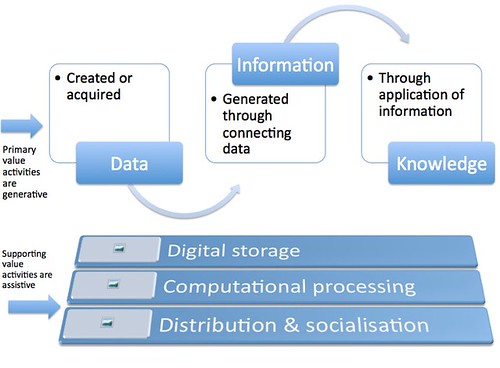

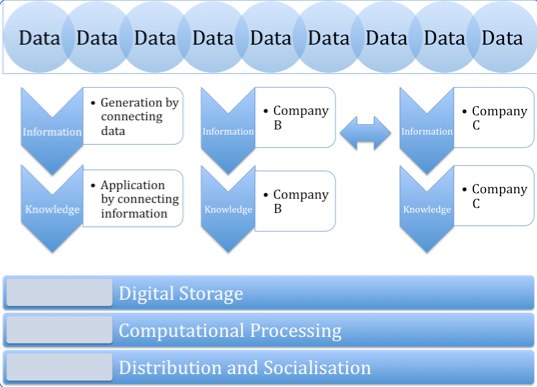

Figure 1: Information Value Chain

The information value chain recognises the value activities required in the use of information. It represents the cycle of a common information product, with the activities most likely undertaken by one entity.

The activities can be broken down into two components within the value chain.

1) Primary value activities relate to aspects of the chain that are the core information product. They are data creation, information generation, and knowledge application.

2) Supporting value activities relate to aspects of the chain that assist the core information product. They are storage, processing, and distribution.

As an example of the above, a photo can be a core information product — with a single image being “data”. The adding of EXIF data, titles, and tags creates information as it enables additional value unlocked in the context of the core information product (the photo).

Knowledge is created when the photos are clustered with other similar photos, like a collection of photos from the same event. Each of the information products may present their own information value, but in the context of each other, they reveal a story of the time period when the pictures where taken — unlocking additional value.

The secondary activities of storage, processing, and distribution of the information product are integral to it. However, they are merely a process that assist in the development of the product and as such are not to be considered the core activities.

Another point to note is that these secondary processes can occur at any three stages of the information process. Computing processing is required when a photo is taken (data creation), when it is edited with additional information like a title (information), and when it is grouped with other photos with similar characteristics (knowledge). Similarly, cloud computing storage or local storage is required for any of those three stages of the information product, with distribution necessary at any stage as well.

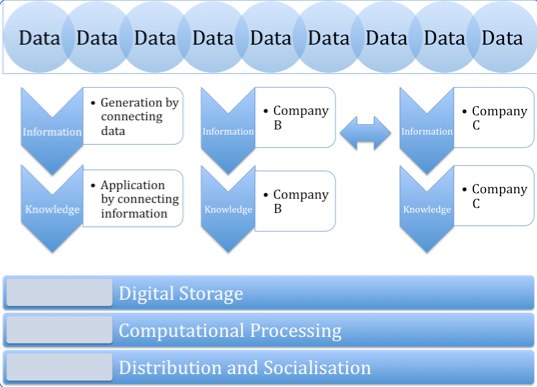

Figure 2: Information Value Network

Whereas the information value chain describes the activities of an information product, it does not acknowledge the full environment of an information product. Information is an intangible good that is utilised by humans (and with increased sophistication over time, by machines) to assist in their own internal thinking. It does not live in isolation, and its presence alongside other information products and their value development cycles can have a huge impact.

In the diagram above, the information value chain has been extended when looking at the context of multiple entities.

In the network, several entities may agree to exchange information products created through their own respective activities, in order to add additional value to each other. Information and knowledge both derive their value from having as many sources as possible; whether it be data sources, but also processed data in the form of information.

Extending the photo example use earlier, another entity may have created an information product relating to geolocation. It has acquired the geo-coordinates of regions, presented them in the appropriate geo standards, and placed them on a map. The owner of a set of activities that generated the photo, can match their geodata to this other activity process and have the photos mapped by location — as well as analysis or specific types of visualisation that can be can be done due to proximity with other photos.

Background to the concepts supporting the theory

Comparative advantage

The law of comparative advantage in international trade states that, if a country is more productive producing one good over another country, it should focus on allocating its resources to that production. Further, if a country has an absolute advantage producing multiple goods, it should focus only on the one where it yields the most productive capacity.

By specializing in producing the products with the higher comparative advantage — even if they across the board are the most efficient at doing them all — the world can expand total world output with the same quantity of resources due to specialisation.

Value chain

A Value Chain Analysis describes the activities that take place in a business and relates them to an analysis of the competitive strength of the business. It is one way of identifying what activities are best undertaken by a business and which are best provided by others (ie, out-sourced).

It helps a company look are what its core competitive advantage is, and segments the activities surrounding its competitive advantage, in order to realize efficiencies and better value creation.

Data, Information, and knowledge

Data can be defined as an object that represents something. Typically data lacks meaning, although it derives meaning when context is added.

Information on the other hand, is what is considered when connecting different data objects — the actual linkages between data objects are what is information. Meaning can be derived through the context of data.

Likewise, knowledge is the extension in this chain of development. That being, the application of information in the context of other information.

Comment on the economic incentive for firms

Industries that operate with the purpose of generating, managing or manipulating information products will benefit by working with other like organisations. It reduces cost, increases engagement, and more fundamentally will increase total value creation.

Cost

By focusing on what an entity has a comparative advantage in and identifying its true competitive advantage, it can focus its resources on the activity that ultimately maximise the entity’s own value.

Take as a case in point a photo sharing website, that is aiming to be both a storage facility (ie, ‚”unlimited storage”) as well as a community site.

- Feature development: Development resources will face competition to build functionality for the photo service, to cater for two completely purposes. This will lead to opportunity cost in the short-term, and potentially the long term if dealing in a highly competitive market.

- Money: Any resource acquisition, whether it be external spending or internal allocations, face conflict as the company is attempting to win on two different types of businesses

- Conflict of interest: The decision makers at the company do not have aligned self interest and face conflict. For example, if a user puts their photos at a pure storage service, management will do what they can to maximise that core value. If the company also does community, management may trade storage value (such as privacy) for the benefits of building the other aspect of the business.

Engagement

In the context of web services, engagement of a user is a key priority. Economic value can be derived by a service due to attention, conversion, or simply a satisfied customer through the experienced offered.

If a service provider focused on their core competency, value can be maximised both for a users engagement and a provider’s margin.

A commerce site aims to convert users and make them customers through the purchase of goods. Commerce sites rely on identity services to validate the authenticity of a user, but it’s not part of their core value offering. In the case of one business, the web designers took away the Register button. In its place, they put a Continue button with a simple message: “You do not need to create an account to make purchases on our site. Simply click Continue to proceed to checkout. To make your future purchases even faster, you can create an account during checkout.”

The results: The number of customers purchasing went up by 45%. The extra purchases resulted in an extra $15 million the first month. For the first year, the site saw an additional $300,000,000.

The significance of this is that by attempting to manage multiple aspects of the experience of their users, this business actually lost potential business. If they integrated their commerce site with an identity site experienced in user login, they may have leveraged this expertise a lot earlier and minimised the opportunity cost.

Value creation

Continuing the example of a photo, let’s assume multiple services work together using the same photo, and that there is full peer-to-peer data portability between the services.

The popular social-networking site Facebook described a technique where they were able to speed up the time they served photos to their users. In a blog post, they state that by removing the EXIF data — metadata that describes the photos (like location, shutter speed, and others — they were able to decrease the load on the servers to produce the photo.

This is fine in the context of Facebook, where the user experience is key and speed matters. But if a person uploaded their photos there as their only copy, and they wanted to use the same photos in a Flickr competition — whose community of passionate photographers puts a different criteria on the photos — they would be at a loss.

In a world that has true data portability, the photos (say the RAW images) could be stored on a specialised storage solution like Amazon S3. The online version of Photoshop could edit the RAW images to give an enhanced quality image for the Flickr community; whereas Google App engine could be used for a mass editing that is computer-intensive, in order to process the multiple RAW photos into EXIF-stripped images for distribution within Facebook. The desktop application Cooliris could access the newly edited photos that still retain their EXIF data, and have them visualised in its proprietary software, which gives a unique experience of viewing the information product.

The significance of the above example is that each service is using the same core information product, but for a completely different purpose. On the surface, all services would appear to be competing for the information product and “lock in” the user to only use it on their service. But the reality is, better value can be generated with their peered data portability. And in some cases, greater efficiencies realised — allowing the web services to focus on what their true comparative advantage is.

Comment on value-creation versus value-capture

This paper makes a explicit explanation on how value is generated. It does not, however, explain how that value can be captured by firms.

It is beyond the scope of this particular discussion to detail how value capture can occur, although it is an important issue that needs to be considered. Web businesses repeatedly have proven to fail to monetise on the web effectively.

This however is more a industry issue than a specific issue related to openness, and this paper makes the case of firms to focus on their core competitive advantage rather than how to monetise it. Instead it suggests that more firms can monetise, which creates total economic output to increase. How the output is shared amongst market participants is a matter of execution and specific market dynamics.