Have you ever wondered who decided to add that question when filling out a form? If you have, like me, then maybe you’ve also thought, what’s the hidden force influencing what we think, say, and do? A thinker, Curtis Yarvin, has a hypothesis that has had me thinking for a while now.

The default answer people give is “the government”. But Yarvin makes an interesting point. Governments, such as that “beacon of freedom” like America or that reincarnation of evil in Putin’s Russia (quotation marks to make you aware, we’ll get to this later), work very differently, to say a small business. They do what he calls bottom-up decision-making. That is to say, by the time it lands on President Biden or Putin’s desk, it’s because it is escalated as a problem. Or rather, a decision that someone below wanted to avoid making. Meaning a lot of decisions happen by the little people. Governments “leak power”.

So where do the little people who make these decisions get their ideas from?

The Cathedral

Yarvin invokes European medieval trauma by naming these influencers “the Cathedral”. A group of unaccountable thinkers who pass their ideas onto the media and high society for digestion and who then poo it out onto the rest of us to gobble on. Like the Catholic Church of the past, you cannot criticise them (or they will gobble you up).

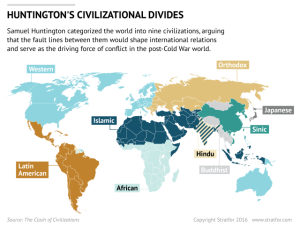

So who is the Cathedral? Academia comes up with the thought and the media propagates it. People with the profession (or the time) to write and publish opinions. And so drives Yarvin with his authoritarian fan base to an accepted conservative view: blame the universities! Those damn bastions of lefty talk. In America, this is the source of the culture war or at least where pronouns are defined. In Russia, Alexander Dugin has been called Putin’s brain, and his work lays out Eurasia’s remaking of the world order that is shifting before our eyes.

But not so fast, Yardin: it takes work to popularise new ideas in universities, and it’s brutal. Something just did not click for me in what is an otherwise thought-provoking analysis of Western society. That’s because experts are people trained in its conventions and practices, meaning new ideas face resistance. How does a professor bootstrap support in their new ideas?

She could write some books. He could donate to some groups and encourage others to support his views. They might tap into a marginalised group and broker their support for this new worldview through their podcast. Google was built on the idea that good ideas get a lot of citations in universities, so likewise, a website with a lot of links should rise to the top of search results. I don’t know the game for how a professor gets their work cited. But I do know how online marketing works and what is the top search result for nearly every topic in the world.

And click: I finally understood how the Cathedral works.

The editors of human knowledge

Wikipedia is one of the most amazing creations of humankind. Unpaid editors, usually with a pseudonym, write content that synthesises the sum of human knowledge. They do this in two main ways. The first is by curating what academic opinions to include, and the second is the behind-the-scenes discussions that decide what to present, shaping how articles get narrated. It goes deeper than that as well: baked into Wikipedia policies are a set of conventions that reflect a philosophical worldview. For example, the use–mention distinction comes from one of the West’s three main schools of philosophy, an idea that amounts to outright manipulation in my eyes when used for narratives like in the telling of history. (I might write more about that rabbit hole once — or maybe it’s if — I get out of it.)

Wikipedia is the 7th most visited website in the world.

Wikipedia has a dynamic process where articles are rewritten, merged, monitored, and reclassified. It embodies the original hypertext vision of Ted Nelson, whereby knowledge is linked. But what’s Wikipedia and the Cathedral have to do with anything?

Because search engines love content with lots of links. (And so does Artificial Intelligence.)

The machines — search engines and AI — are smart. But it’s not so much that they tell us what to think. Instead, what’s happening is that the machines transmit what one group of humans is saying to the other. Those who create and transmit the knowledge and those who search for knowledge—the everyday intellectual who educates their social group. More impactfully, the profession of journalism– underpaid people, on deadlines — trying to whip some knowledge on a topic quickly. According to the Economist, a newspaper whose business model is to be in every dentist’s office, you’d be surprised how many journalists copy content from what they find on the web, especially Wikipedia. That’s to say directly copying; what I’m talking about is even bigger: it’s the indirect impact,

Play it again, Sam

If I lost you, let’s play this out in sequence.

Step one: The academics produce and publish the ideas in books and journals. “America is a beacon.” Check.

Step two: Wikipedia’s community cherry-picks the knowledge by adding it randomly or through intense debates behind the scenes reverting someone’s edit. “America is a beacon that has consensus by people we deem to matter”. Check.

Step three and four: Search engines capture Wikipedia on any topic journalists use for background reading, and it narrates their writing. “America, widely accepted as a beacon…”

Steps 5 to 89: The content journalists generate transmits to dentists, government administrative staff, and beyond where pictures of beacons bamboozle the public. People talk about it on social media (“beacon! beacon! beacon!) and the media keeps talking about it, which feeds the academics to keep writing and shifting their practices that define the standards (“We evaluated 112 studies in pre-prints and with a badass new regression model have determined beacon is what fly-eating plants imply when prodded to describe America’s free society”). And like a virtuous cycle, these ideas eventually morph into the new conventions of the day. With the Wikipedia editors ready to upgrade it from a footnote to a lead sentence. And when the deputy assistant of forms uses a search engine, they see all the results with a concise, authoritative summary from Wikipedia, giving them the confidence to use beacon.

It’s a process. The sausage does not get made overnight. But that, in my unprofessional opinion, is how we get told what to think as free citizens of democracies. What’s my advice for the next time you see a weird question appear on a form?

Yell out the word beacon. It may make you feel better.