Last year for my birthday, my amazing wife treated me to a course I wanted to do. (It’s still being offered, on business writing and story telling, and I highly recommend it .) I’ve always been interested in good writing, and in my teenage years, I studied The Economist’s style guide like a bible. So this was an absolute treat for me.

As part of the course, we had an ongoing assignment. I picked a meaty international relations topic in an area I’ve always wanted to understand better: the relations between Greece and Turkey. Despite being complex, I made sense of it and produced something I was quite happy with.

It had a very important message. I was reminded of it as I read the news about the upcoming presidential election in Turkey. I thought I’d dust off the cobwebs on this blog and publish it.

Introduction:

Greece and Turkey’s strategic rivalry is getting more intense and more dangerous. The geopolitics of energy to Europe has reframed their old issues and may instead shape their resolution, increasing the probability of war.

Executive summary

Relations have gotten more complicated since the 1980s for historic rivals Greece and Turkey. Needless to say, it’s still about who has control over the Aegean and the eastern Mediterranean. While Cyprus and rights over the Aegean Sea remained unresolved, energy politics is framing the rivalry as one of intense regional energy competition.

The main article

In recent decades, relations have become entangled for old rivals Greece and Turkey. However, it’s still about who has control over the Aegean Sea and the eastern Mediterranean. Since the 1990s, the countries have pursued a strategy of encircling each other, which has made their conflict expand to other countries — and pulled in the EU. While Cyprus and rights over the Aegean remain unresolved, the discovery of hydrocarbons reframes their disputes. And importance.

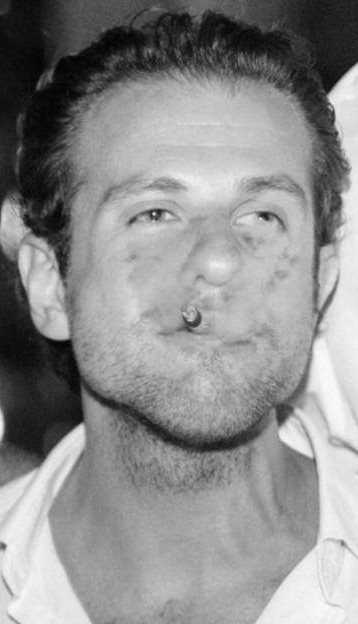

In 1986 by the border at the Evros River, a Greek soldier was shot after an offer to trade cigarettes. His death sparked outrage. In 1987, a Turkish survey ship, the Simsik, was ordered to be sunk to the bottom of the Greek waters if it floated too close. It nearly did. In 1995 the uninhabited rock island Imia, where both countries claim jurisdiction, had them close to starting a war.

The problem has grown. Lesser incidents often occur — where both sides exchange fire — which does not help when tensions fly high. Each country has become the other’s most visible threat. Yet despite busy newsrooms, the olives this harvest have not all been bitter.

The good old days

In 1995, relations began to change with the Greek election of Kostas Simitis, who redefined priorities. In 1998, the capture of the Kurdish separatist Abdullah Ocalan – on the way from the Greek embassy in Kenya – and the related fallout led to the Greek foreign minister resigning, whose replacement was with a cheer squad member for discussions with Turkey. In 1999, violent earthquakes hit both countries and saw an outpouring of goodwill.

In the years that followed, relations improved. They included agreements on fighting organised crime, reducing military spending, preventing illegal immigration, and clearing land mines on the border. More significantly, Greece lifted its opposition to Turkey’s accession to the EU, bringing some Turkish delight. However, even though there was a change to the weather, it did not change the atmosphere on the issues that mattered.

The Aegean conflict: a negotiation minefield

The UN sea treaty UNCLOS evolved in 1982 and came into force in 1994. Turkey is not a signatory. The conflict is whether the Greek islands are allowed a continental shelf, the basis of claiming rights over the sea. Turkey disputes that Greece can claim 12 miles off the coast of their islands, which the sea treaty permits, implying only the mainland has this right.

There’s a good reason why this definition matters. It would restrict Turkey and give Greece dominant control of the Aegean. The EU requires the sea treaty’s membership as a pre-condition. Turkey on the other hand, has made a continental claim to split the Aegean Sea in the middle.

There are several issues at stake based on how this continental shelf is defined. One is protecting Turkey’s shipping lanes as the Dardanelles feed into the Aegean (despite international law protecting this). A second is on the rights to mineral wealth (which has yet to be found). A third is on the 1950s flight zone, which impacts the military (a non-issue that was challenged two decades later, after the Cyprus invasion, to match the continental shelf claim by Turkey). Ultimately, fear of sovereignty loss is what’s driving this conflict. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the Greek reaction with the 1974 militarisation of the Greek islands near Turkey, and the Turkish creation of the 1975 Izmir army base (as large as the entire Greek army itself with amphibious capabilities) has created permanent military tensions.

Cyprus and the EU: elephants in the room

Cyprus remains a significant issue. The 1990s saw EU accession friction which was parallel to military tension. In 1994, Greece and Cyprus agreed on a security doctrine that would mean any Turkish attempt on Cyprus would cause war for Greece. In 1997 Cyprus purchased two Soviet-era missile systems, the S-300s, letting out a Turkish roar; Greece did a swap and installed them on Crete against heavy whimpering. Negotiations never settled the division on the island in the 1990s because of the non-negotiable by the Turkish side to recognise North Cyprus as an independent state. When Cyprus joined the EU in 2002, the negotiation took a different flare. With Greece and Cyprus as EU members, this has become an EU issue; but with the island only 60 miles from Turkey, it also remains a national security issue for Turkey.

Concerns about Turkey like its human rights record and Greece’s veto ultimately had Turkey side-lined by the EU. Domestically, this contributed to the shift away from Turkey’s founding secular doctrine Kemalism and the rise of political Islam. The change was popular in inland Turkey because it adjusted the government’s amnesia of the Ottoman Empire’s past. It also evolved to an alternate identity of European orientation, as a regional center in the emerging Eurasian political formation.

In recent years, the Blue Homeland policy of Turkey positions it in the Mediterranean as a sea power. Greece’s fear, often explicitly communicated by Turkey’s politicians in the media, is that Turkey wants to renegotiate the Treaty of Lausanne. A treaty that created Turkey the country from the remnants of the defeated Ottoman Empire and defined its modern borders.

Pass the gas, please.

The countries have pursued a strategy of encircling each other. Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, both Greece and Turkey viewed each other with suspicion as they developed relations with the new countries. It wasn’t until 1995, however, that this fear materialised. Greece formed a defense cooperation agreement with Syria and between 1995-1998 established good relations with Turkey’s other neighbors, Iran and Armenia. In reaction, Turkey spoke with Israel in 1996, which caused outroar by the Arab countries.

The 2010 discovery of gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean first by Israel and then Egypt, has created new energy to fan the disputes. The historical security issues of the Aegean and Cyprus are now a focal point to resolving Europe’s energy needs. For example, the 2016 Turkey-Israel reconciliation led to Greece torpedoing the 2017 Cyprus UN talks due to their relationship’s risk for developing a gas pipeline. In 2019, the east Mediterranean gas forum was created, including seven countries but excluding Turkey. Turkey would work from 2018 with Libya to extend its economic rights over the sea, which has led to recent tensions with other members of the EU. This instability over the status of the Aegean and Cyprus prevents the needed investment from developing pipelines to Europe.

The region is considered the end-point for east-west pipelines. One of these originates in the remote Caspian Sea, one of the oldest oil-producing regions: it still has 48 billion barrels of oil in proven and probable reserves. That’s comparable to one year and a bit of global oil consumption. Its 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas is enough to satisfy two years of global gas consumption. The opening up of these fields is recent after more than 20 years of negotiation following the 2018 A Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea.

Like the Balkan wars of 1912 that helped trigger World War 1 and the proxy wars in the 1940s in Greece that sparked the cold war, this region and Greece and Turkey’s local conflict have the potential to spill over. This is because the distribution of that gas is dependent on the shipping lanes and pipelines that go through Turkey and Greece. With Russia’s actions in Ukraine having Europe question where its gas comes from, expect their old issues to flare up. Let’s hope without adding gas to the regular fire sparks that occur.